By Sharon Batiste Gillins

Genealogist

Mid-June in the year of our Lord, 1865, was so typical of Galveston in late spring. Families were going about their lives, businesses were operating, steamers went in and out of port, and merchants were selling goods. Farmers in the Houston area had welcomed days of rains that quenched corn crops, but the Island had been parched dry for weeks with no more than a sprinkle since the month began. The moon languished in its last quarter. Despite the apparent routine, this period in time was like no other in American history and life in Galveston, in Texas and in the nation would never be the same.

Mid-June in the year of our Lord, 1865, was so typical of Galveston in late spring. Families were going about their lives, businesses were operating, steamers went in and out of port, and merchants were selling goods. Farmers in the Houston area had welcomed days of rains that quenched corn crops, but the Island had been parched dry for weeks with no more than a sprinkle since the month began. The moon languished in its last quarter. Despite the apparent routine, this period in time was like no other in American history and life in Galveston, in Texas and in the nation would never be the same.

In the days and weeks that led up to the 19th of June, the newspapers were filled with the latest stories, reports and editorials about the end of the War, the beginning of the peace and the imminent freedom of the enslaved Africans. On June 14th, the Galveston Daily News reported that federal troops would soon arrive in Galveston. The announcement quickly spread throughout the white and black communities and the city’s residents were overcome with a curious mix of anticipation and anxiety. Uncertainty permeated the air as they contemplated the consequences of the Civil War’s end and the arrival of Federal troops into the city. Each segment of the population experienced a different set of emotions, the unknown and imagined consequences dissected in print from every angle. That is, every angle except that of the enslaved people whose destiny and very lives would be most impacted.

With the knowledge that they would soon be freed from bondage, one can imagine that enslaved blacks anticipated sweet freedom but must have worried about their future status and livelihood. Former Confederate soldiers on the Island were anxious and angry about President Andrew Johnson’s Amnesty Proclamation, a document they were being compelled to sign and swear to in order to establish their loyalty to the Union. Undoubtedly, they would have conflicts of conscious and practicality when choosing between loyalty and treason. Businessmen whose profits had been disrupted for years wanted to get back to profitable operations, but they were anxious about currency…what money would they use? No provisional government had yet been established in Texas, leaving city leaders, under the direction of Mayor C. H. Leonard, unsure of what their authority would be after the Federal troops arrived. So palpable was the uncertainty that the Galveston Daily News re-printed an article from the New Orleans Times-Picayune that was obviously meant to uplift citizens and calm fears about the future: “The first duty incumbent on us is to refute and dissipate the doubts, fears and dark forebodings of those who, influenced by the spectacle of the great ruin and disorder created by the war, too easily exaggerate their extent and too easily incline to despair.”

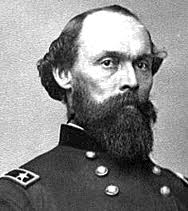

In the midst of such widespread emotional upheaval, Galveston’s population changed both suddenly and dramatically. Every seat on every train from Houston was packed with passengers; some were returning residents and some were newcomers who had chosen this promising and prosperous place to cast their new lot. The streets swelled with an influx of people. Three days after it was announced in the newspaper, the first Federal Troops began arriving in the city by steamer. Some three to four hundred people gathered on the wharf and warmly welcomed the troops’ arrival with hopes of relief from the uncertainty and suspense that gripped the city. A band played “Yankee Doodle”, a song probably not heard in Galveston in recent years. Only a day later, on the 18th, four army transports with troops from Mobile added to their numbers. The steamer Clinton carried over 2,000 soldiers from the 13th Army Corps, the 34th Iowa regiment, the 83rd Ohio regiment and part of the 94th Illinois regiment. Regiment officers announced that Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger was in command of the troops and was due to arrive in Galveston any time. One of the first tasks of Granger’s advance staff was to prepare for arrival of the Parole Commissioner who would be responsible for administering the Amnesty Proclamation and pardoning Confederate soldiers.

The city’s landscape was also undergoing rapid change. Every street was bustling with hammers, nails and saws as returning homeowners hustled to repair their damaged or looted property. With all the new residents and arriving troops, housing was at a premium; new construction, higher rents and boarding in homes became the norm.

Soldiers were everywhere, encamped in tents on the Public Square (site of the old Galveston Courthouse) and quartered in the cotton presses. At one time, as many as 15,000 troops were in Galveston, most on their way to inland locations to establish posts. Two transports arrived carrying colored troops headed for the Rio Grande. The sight of black men in uniform would have been inspiring to some, repulsive to others, and an uncommon spectacle to all. Such radical changes were overwhelming to Galveston residents.

On June 19th, Granger arrived in port aboard the U.S. steamer transport Crescent and would assume command of all the troops in Texas. He wasted no time upon his arrival, establishing the headquarters of the 13th Army Corps in the Osterman Building located at the corner of Strand and 22nd Streets. His officers quickly informed Galveston’s mayor that the Federal troops had no desire to interfere with the daily operation of the city and welcomed their full cooperation and support for the changes about to occur.

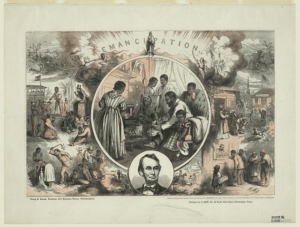

Granger then issued five general orders to the citizens of Galveston on that day. The most significant of these was General Order Number 3 which essentially ended the practice of slavery for 250,000 enslaved blacks in Texas, the last freed in the U.S. The order read: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

The announcement of freedom brought the eruption of spontaneous celebrations by freedmen and their supporters throughout the city, from the docks to the Public Square, in churches, on street corners and in homes. In the days and weeks to follow, blacks and whites, Union and Confederates struggled to establish a new normal. Life as they knew it had changed for everyone.

The moon exited its last quarter that week in June and entered a new moon. So too, Galveston and the nation left behind a sad chapter in its history and entered a new era that brought the Union closer to its founding principles…freedom and equality for all.

The Galveston Daily News found reason for a positive outlook, as within days, a refreshing, cleansing rain fell upon the city “ensuring an abundant harvest and changing the atmosphere to somewhat of a living temperature.”

Sharon Batiste Gillins is a native of Galveston who has been involved in genealogical research over the past 25 years. She earned a Bachelor’s degree at Howard University and Master’s Degree at the University of the District of Columbia. Her career spans over 40 years in education, retiring as Associate Professor at Riverside (CA.) Community College. She frequently presents workshops and delivers courses at regional and national genealogy conferences, among them the National Genealogical Society, Federation of Genealogical Societies, International Black Genealogical Summit, and the Creole Family History Conference. She has served as adjunct faculty at Institute of Genealogy and Historical Research since 2006 and is also on faculty for the Alabama State University Genealogy Colloquium in Montgomery, AL. At present, Ms. Gillins is a Research Associate at the Mary Moody Northen Endowment in Galveston where she is responsible for the Moody family and business archive of manuscripts and photographs that date to the early 1800s.

References:

• Galveston Daily News, June, 1865

• Hays, Charles W. Galveston- History of the Island and the City. Jenkins Garrett Press. Austin Texas 1974.

• Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph, June, 1865.

• New Orleans Tribune, June 18, 1865.

• The Texas Almanac for 1865, Book, 1864; (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth123771/ : accessed December 01, 2014), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Texas State Historical Association, Denton, Texas.

• Special thanks to the Rosenberg Library Galveston and Texas History Center and the Mary Moody Northen Endowment Center for Twentieth Century Studies.

Click edit button to change this text.