The Many Lives of Pauli Murray

She was an architect of the civil-rights struggle, the women’s movement, and the first African-American woman vested as an Episcopal priest. Why haven’t you heard of her?

(The New Yorker) The wager was ten dollars. It was 1944, and the law students of Howard University were discussing how best to bring an end to Jim Crow. In the half century since Plessy v. Ferguson, lawyers had been chipping away at segregation by questioning the “equal” part of the “separate but equal” doctrine—arguing that, say, a specific black school was not truly equivalent to its white counterpart. Fed up with the limited and incremental results, one student in the class proposed a radical alternative: why not challenge the “separate” part instead?

That student’s name was Pauli Murray. Her law-school peers were accustomed to being startled by her—she was the only woman among them and first in the class—but that day they laughed out loud. Her idea was both impractical and reckless, they told her; any challenge to Plessy would result in the Supreme Court affirming it instead. Undeterred, Murray told them they were wrong. Then, with the whole class as her witness, she made a bet with her professor, a man named Spottswood Robinson: ten bucks said Plessy would be overturned within twenty-five years.

Murray was right. Plessy was overturned in a decade—and, when it was, Robinson owed her a lot more than ten dollars. In her final law-school paper, Murray had formalized the idea she’d hatched in class that day, arguing that segregation violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution. Some years later, when Robinson joined with Thurgood Marshall and others to try to end Jim Crow, he remembered Murray’s paper, fished it out of his files, and presented it to his colleagues—the team that, in 1954, successfully argued Brown v. Board of Education. (read more)

Rare Photos Show Lesser-Known Black Women Activists Of The 19th Century

(The Huffington Post) When discussing black women’s history, activists like Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks are often quick to come to mind for many.

(The Huffington Post) When discussing black women’s history, activists like Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks are often quick to come to mind for many.

Yet while their resilience and advocacy is noteworthy, they’re certainly not the only famous black activists we should know.

Now, a recently digitized collection of rare photos at the Library of Congress shows similarly socially active but lesser-known black women throughout the 19th century. The images, which are mostly striking black-and-white portraits, once belonged to William Henry Richards, a professor who taught at Howard University Law School for nearly four decades before his death in 1951. Richards was “active in several organizations that promoted civil rights and civil liberties for African Americans at the end of the nineteenth century,” Beverly Brannan, the curator of Photography, Prints & Photographs Division at the Library of Congress wrote in a post published last week.

The library acquired the collection in 2013 and recently digitized the images to bring visibility to more obscure black women who were active in civil rights, education and journalism in the decades following the Civil War. They include pictures of women like writer Hallie Quinn Brown, who helped to launch the Colored Women’s League of Washington, DC and educator Josephine A. Silone Yates, who was trained in chemistry and was one of the first black teachers at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. (view the images)

Photo: Lillian Parker Thomas (born 1857) was a journalist and correspondent editor for the Freeman, which is recognized as the first illustrated black newspaper. She has been described in history books as “the mantle of mental achievement” and her role was one held by no other woman on staff at the publication.

Morris Brown College used to enroll 2,500 students — today, there are 40

After losing accreditation and selling buildings, officials at the school—the first institution of higher learning in Georgia founded by black people, for black people—say it’s rebuilding.

(Atlanta Magazine) In recent years Morris Brown has taken on the feel of an old battleship gradually being decommissioned, manned by a skeleton crew. But school officials insist that though it’s been down, Morris Brown is far from out—and that a rebirth is close at hand. Faith abounds, but is it enough?

(Atlanta Magazine) In recent years Morris Brown has taken on the feel of an old battleship gradually being decommissioned, manned by a skeleton crew. But school officials insist that though it’s been down, Morris Brown is far from out—and that a rebirth is close at hand. Faith abounds, but is it enough?

Morris Brown was born from audacity. On a winter’s day in 1881, local African Methodist Episcopal clergy, many of whom had been born into slavery, gathered in Big Bethel AME Church in the Old Fourth Ward. Clark College, a school for black students founded by white Methodist missionaries, needed their help to “furnish a room” on the Clark campus. But the clergy had other ideas; they decided to open their very own college instead.

A three-year fundraising campaign, fueled mostly by contributions from Georgia AME churches, helped raise the $13,000 needed to buy property and build a school named for Morris Brown, an AME bishop who fled to Philadelphia from Charleston in the 1820s after being accused of plotting a slave revolt. Morris Brown opened its doors in the Old Fourth Ward on October 15, 1885, to 107 middle, high school, and college students.

“Morris Brown College was there to provide them an opportunity,” says Henry Porter, a longtime math professor who has forgone a paycheck since 2003 out of love for the school. “If you really wanted to go to school, you could get that opportunity at Morris Brown College. It allowed folks just out of slavery to get an education.” (read more)

Photo: Built in 1882, Fountain Hall once housed classrooms and offices—including one used by civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois when he taught at Atlanta University, which previously occupied the campus. After Morris Brown lost accreditation in 2003, the landmark building was shuttered. Its classrooms now serve as storage. Photograph by Audra Melton

US Mint Releases Frederick Douglass Quarter

Legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass is now on a U.S. quarter.

Legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass is now on a U.S. quarter.

The United States Mint released the coin on (April 4).

The coin, made of nickel and copper, shows the author writing in front of the Southeast Washington, D.C., home where he lived from 1877 to his death in 1895.

The quarter is available to order online, and it’s headed into mainstream circulation, a U.S. Mint spokesman said. Eventually, about 400 million Frederick Douglass quarters will be in circulation, the spokesman said. (read more)

Literary: “The Black Officer Corps, A History of Black Military Advancement from Integration through Vietnam”

The U.S. Armed Forces started integrating its services in 1948, and with that push, more African Americans started rising through the ranks to become officers, although the number of black officers has always been much lower than African Americans’ total percentage in the military. Astonishingly, the experiences of these unknown reformers have largely gone unexamined and unreported, until now.

The U.S. Armed Forces started integrating its services in 1948, and with that push, more African Americans started rising through the ranks to become officers, although the number of black officers has always been much lower than African Americans’ total percentage in the military. Astonishingly, the experiences of these unknown reformers have largely gone unexamined and unreported, until now.

The Black Officer Corps traces segments of the African American officers’ experience from 1946-1973. From generals who served in the Pentagon and Vietnam, to enlisted servicemen and officers’ wives, Isaac Hampton has conducted over seventy-five oral history interviews with African American officers. Through their voices, this book illuminates what they dealt with on a day to day basis, including cultural differences, racist attitudes, unfair promotion standards, the civil rights movement, Black Power, and the experience of being in ROTC at Historically Black Colleges, including Prairie View. Hampton provides a nuanced study of the people whose service reshaped race relations in the U.S. Armed Forces, ending with how the military attempted to control racism with the creation of the Defense Race Relations Institute of 1971. The Black Officer Corps gives us a much fuller picture of the experience of black officers, and a place to start asking further questions.

“Drawing on numerous primary and secondary sources, The Black Officer Corps chronicles the tremendous struggle waged by African Americans to prove their worth as leaders in peace and war. Hampton has written a detailed and highly readable narrative tracing the black office’s experience from the American Revolution, through the 1980’s. It is an informative and valuable resource for the general reader of black military history.” — James E. Westheider, author of “Fighting in Vietnam: The Experiences of the U.S. Soldier.”

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Cougars of Any Color,” by Katherine Lopez (2008).

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Cougars of Any Color,” by Katherine Lopez (2008).

After years of playing sub-par teams in weak athletic conferences, the University of Houston athletic program sought to overcome its underdog reputation by integrating its football and basketball programs in 1964. Cougar coaches Bill Yeoman (football) and Guy V. Lewis (basketball) knew the radical move would grant them access to a wealth of talented athletes untouched by segregated Southern programs, and brought on several talented black athletes in the fall semester, including Don Chaney, Elvin Hayes, and Warren McVea. By 1968, the Cougars had transformed into an athletic powerhouse and revolutionized the nature of collegiate athletics in the South.

This book gives the Cougars athletes and coaches the recognition long denied them. It outlines the athletic department’s handling of the integration, the experiences of the school’s first black athletes, and the impact that the University of Houston’s integration had on other programs.

This Week in Texas Black History, Apr. 16-22

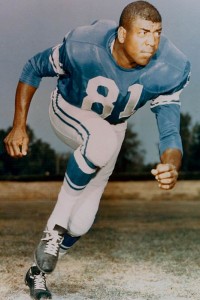

16 – National Football League defensive back Dick “Night Train” Lane was born in Austin on this day in 1928. After serving in the Army during World War II and the Korean War, Lane was signed as a free agent in 1952 with the Los Angeles Rams, though he’d only played at Austin Anderson High School and Scottsbluff (Neb.) Junior College. During his 13-year career, Lane was known as ferocious, intimidating hitter and was responsible for the banishment of the clothesline tackle. Lane’s 14 interceptions in 1952 still stands as an NFL record for rookies. In 1969, just four years after his retirement, he was voted the best cornerback in the first 50 years of the NFL, and in 1974 was inducted to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In 2001, he was inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame.

16 – National Football League defensive back Dick “Night Train” Lane was born in Austin on this day in 1928. After serving in the Army during World War II and the Korean War, Lane was signed as a free agent in 1952 with the Los Angeles Rams, though he’d only played at Austin Anderson High School and Scottsbluff (Neb.) Junior College. During his 13-year career, Lane was known as ferocious, intimidating hitter and was responsible for the banishment of the clothesline tackle. Lane’s 14 interceptions in 1952 still stands as an NFL record for rookies. In 1969, just four years after his retirement, he was voted the best cornerback in the first 50 years of the NFL, and in 1974 was inducted to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In 2001, he was inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame.

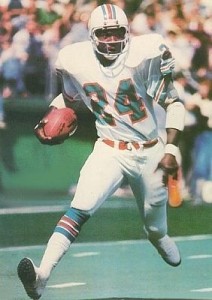

17 – Two-time All-Pro running back Delvin Williams was born on this day in 1951 in Houston. Williams graduated from Kashmere Gardens High School in 1970 and was a Parade Magazine All-American and one of the most sought after prep running backs in the country, recruited by every major college football program. Williams chose the University of Kansas and four years later became a second round pick of the San Francisco Forty-Niners. He thrived in the National Football League for eight seasons, becoming the first player in NFL history to rush for 1,000 yards in a season for two different teams (Niners and Miami Dolphins). Williams was also the first player in NFL history to set rushing records for two different teams, and to be named to the Pro Bowl for both an AFC & NFC team.

17 – Two-time All-Pro running back Delvin Williams was born on this day in 1951 in Houston. Williams graduated from Kashmere Gardens High School in 1970 and was a Parade Magazine All-American and one of the most sought after prep running backs in the country, recruited by every major college football program. Williams chose the University of Kansas and four years later became a second round pick of the San Francisco Forty-Niners. He thrived in the National Football League for eight seasons, becoming the first player in NFL history to rush for 1,000 yards in a season for two different teams (Niners and Miami Dolphins). Williams was also the first player in NFL history to set rushing records for two different teams, and to be named to the Pro Bowl for both an AFC & NFC team.

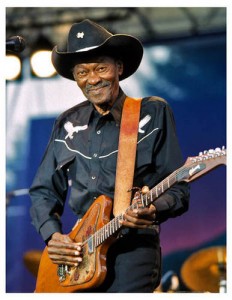

18 – On this day in 1924, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown was born in Vinton, Louisiana. Brown was raised in Orange, Texas where he learned to play several instruments beginning with fiddle at age 5, followed by guitar, mandolin, viola, harmonica, and drums. Brown got his nickname from a high school teacher who said he had a voice “like a gate.” He made dozens of recordings in the 1940s and ’50s, including many regional hits – “Okie Dokie Stomp,” “Boogie Rambler,” and “Dirty Work at the Crossroads.” He was nominated six times for Grammy Awards and was awarded one in 1983 in the “Traditional Blues” category for his album, “Alright Again.”

18 – On this day in 1924, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown was born in Vinton, Louisiana. Brown was raised in Orange, Texas where he learned to play several instruments beginning with fiddle at age 5, followed by guitar, mandolin, viola, harmonica, and drums. Brown got his nickname from a high school teacher who said he had a voice “like a gate.” He made dozens of recordings in the 1940s and ’50s, including many regional hits – “Okie Dokie Stomp,” “Boogie Rambler,” and “Dirty Work at the Crossroads.” He was nominated six times for Grammy Awards and was awarded one in 1983 in the “Traditional Blues” category for his album, “Alright Again.”

21 — This date marks the commemoration of the song The Yellow Rose of Texas. The song grew out of the Battle of San Jacinto when Texas forces led by Sam Houston defeated the Mexican troops of Gen. Santa Anna in 1836 and won Texas’ independence from Mexico. The song is a tribute to a woman (Emily West) who supposedly “entertained” the Mexican general, delaying his preparations for the battle, while the Texians successfully attacked and defeated his army in an 18-minute skirmish. However, the woman’s true identity and actual role, if any, in the battle is the subject of great debate. Generally, she is thought to have been a light-skinned mulatto, but other theories say she was Hispanic. The songs’ composer is also a mystery, though its original lyrics seem to suggest a black man:

21 — This date marks the commemoration of the song The Yellow Rose of Texas. The song grew out of the Battle of San Jacinto when Texas forces led by Sam Houston defeated the Mexican troops of Gen. Santa Anna in 1836 and won Texas’ independence from Mexico. The song is a tribute to a woman (Emily West) who supposedly “entertained” the Mexican general, delaying his preparations for the battle, while the Texians successfully attacked and defeated his army in an 18-minute skirmish. However, the woman’s true identity and actual role, if any, in the battle is the subject of great debate. Generally, she is thought to have been a light-skinned mulatto, but other theories say she was Hispanic. The songs’ composer is also a mystery, though its original lyrics seem to suggest a black man:

There’s a yellow rose in Texas

That I am going to see

No other darky (sic) knows her

No one only me

She cryed (sic) so when I left her

It like to broke my heart

And if I ever find her

We nevermore will part.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Holidays,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.